|

|

Ohio66 presents an in-depth look at the circumstances surrounding the departure of George Maharis from route 66 in the middle of the third season.

|

Author John M. Whalen's new novel, Jack Brand, is available now from these retailers: Barnes & NobleAmazon.com |

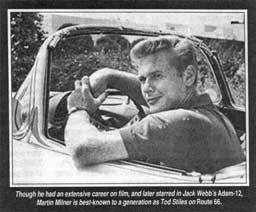

Life on Route 66 with Martin Milner

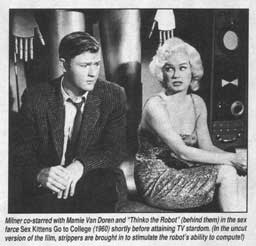

MARTIN MILNER, WHO PLAYED Tod Stiles on the classic TV series Route 66, was a film actor years before the series began, and has had a long career in TV and movies since then. Now 68 and living in San Diego, Milner hosts a popular radio show, Let's Talk Hook-Up, heard in Southern California, and Let's Talk Fishing, syndicated throughout the Western United States. But in this exclusive interview, Milner remembers the four years he sat behind the wheel of the Corvette.

Milner recalls what it was like living on the road, traveling with his family, a housekeeper, and a dog. He describes what the day-to-day operation of the Route 66 traveling production company was like, and remembers the cutting-edge scripts written by series co-creator Stirling Silliphant. He recalls filming episodes where they had only half a script, because Silliphant hadn't finished writing the ending yet, and discusses the real reason why the show went off the air.

Milner can now be seen every night on Nickelodeon's TV Land cable channel in Adam-12. His films, and appearances on Murder She Wrote, Diagnosis Murder, and the RoboCop TV series show up in reruns just about everywhere. But for now, close your eyes, and listen for that signature Nelson Riddle theme, featuring the rolling piano notes and the soaring strings, visualize that white line down the center of the highway moving toward you, as we take a journey back to Route 66.

OUTRÉ: We want to talk mostly about Route 66, but we must mention that you had been acting in films since 1946. Your first film was Life with Father (1947), you were in Sands of Iwo Jima and The Long Grey Line. So you worked with John Wayne, and John Ford. What was that like?

MILNER: Well, I never worked with John Ford and John Wayne together. I worked with John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima, Halls of Montezuma, and in Operation Pacific. Ford came and visited the set on Operation Pacific. I worked with Ford in The Long Grey Line and again in Mr. Roberts.

OUTRÉ: What was your impression of John Ford?

MILNER: He was a tough, gruff old guy, but he was very loyal to the people that were in his - for want of a better word - stock company. Years alter that, when l was doing Adam-12, we heard from his daughter, or secretary - I don't remember now, which - that he enjoyed watching Adam-12. So we invited him to the set and had a chair made for him, and he visited the set for about a half a day, in the early '70s. It was fun to be able to do that with him.

OUTRÉ: Any memories of John Wayne?

MILNER: Well, he was very good to me. I first met him on Sands of Iwo Jima, and then, about a year later, he was making this movie at Warner Bros., Operation Pacific, and I got a call to go into the casting office for a role in that. I was in college at the time, going to USC, and he was there in the casting office, which was kind of a surprise. I expected to have to read, or at least interview for the role. He told me that he wanted me to play the role, and originally there were two Lieutenants JGs on the submarine, but he was taking the two roles and combining them into one, and he wanted me to play it. So he was very good to me.

OUTRÉ: Then in 1960, along came Route 66. How did you get that role?

MILNER: You know, I had just done a couple of pretty good movies. I had done The Sweet Smell of Success, I was under contract to Burt Lancaster - to his company, Hecht-Lancaster - and then they loaned me to Warner Bros. for Marjorie Morningstar. Both of those roles were pretty significant, and Bert Leonard, the producer of Route 66, saw that and asked me to play the role.

OUTRÉ: The other guiding force on Route 66, of course, was Stirling Silliphant. How much of Tod Stiles was written by Silliphant, and how much ot him was Martin Milner?

MILNER: Oh, I think a lot of it was written. There really wasn't very much of me there. As you evolve over the course of the series, more of you creeps into the character. But Stirling Silliphant wrote that character, and identified the character that I played with himself. And Bert Leonard identified with the character that George Maharis played. He was kind of a tough New York kid, Bert Leonard was, and he identified with Maharis, and Stirling Silliphant was kind of well educated, so he identified with the character that I played.

OUTRÉ: Did you get to interact with Silliphant much?

MILNER: Oh, yeah. A lot.

OUTRÉ: I understand that he traveled in advance of the production company, went to the locations, got a feel for the place, and wrote up a script.

MILNER: Right. He wrote specifically for that location, but I saw him a lot. I saw him several times a year, and during hiatus. I knew him well.

OUTRÉ: Did you get much instruction from him on how to play the part, or was that up to the director of each particular show?

MILNER: I don't think I interacted much with him about that. If there was a conflict between me and the director, I could always go to Bert Leonard, or go to Stirling and ask for their input.

OUTRÉ: But he was always traveling, and wasn't on the set.

MILNER: No, he wasn't. And he was always behind. If Stirling had a month to write a script, he'd goof of for three weeks and write it in a week. That was his M.O.

OUTRÉ: So he was something of a procrastinator, but could turn around and get it cranked out by deadline.

MILNER: Exactly.

OUTRÉ: Route 66 was unusual in another regard. The series was filmed entirely on location. Can you describe what that was like, being on the road for four years? You had your family with you.

MILNER: Yeah, I was married, and had begun having a family, so they traveled with me a good bit. And my wife would go home and have a baby. And once the baby was old enough, she'd come out on the road. And it was a propitious time when the series ended, my oldest girl was just ready to start kindergarten. And they wouldn't have been able to travel with me anymore. So it worked out well. We traveled with kids, and a housekeeper. And it was before the days of motor homes and before the days of vans, really. We took our dog with us. It was a circus.

OUTRÉ: Was it basically like a traveling movie studio, traveling from town to town?

MILNER: I don't think you could call it a studio. It was like a traveling location company. We didn't have any sets. We had all the equipment we needed. We filmed in what's called “live sets.” We filmed in actual locations, even interiors on location. We had trucks with equipment. A truck carried two Corvettes and three passenger cars that we used to move cast and crew around.

OUTRÉ: What color were the Corvettes?

MILNER: The Corvettes were a kind of a sand color. Everybody always thought they were red. The first year, it was kind of blue, but in the second year we settled on a beige color, because it photographed well in black-and-white.

OUTRÉ: How did the day-to-day operation actually work?

MILNER: Generally, we did two episodes in one town, to hold the moving down. So we'd go into town, do two episodes, get everything loaded in the truck, and if it was a long move - if, for instance, we were going from Montana to Chicago - the crew, with the exception of the driver, would fly home for a few days. But me and my family would travel with the trucks, because we had the kids with us. We'd just drive to Chicago, and the advance man would have places for us to stay, and we'd start work there.

OUTRÉ: How much in advance would you have the script to prepare for filming?

MILNER: Not very long. There were times when we started a script and didn't know how it ended, because Stirling hadn't written the end yet. I can remember particularly in Cleveland, calling Stirling and saying, “How does this thing end? You know, we gotta know what happens here.” And he'd tell us over the phone.

OUTRÉ: What episode was that?

MILNER: It was an episode with Nehemiah Persoff, “lncident on a Bridge.” It started with a flashback, so it was very difficult not having the end. I mean, not knowing what the end was, because we were starting at the end. So we called Stirling and he gave us the storyline over the phone.

OUTRÉ: So he could write without knowing how the story ends?

MILNER: Well, he knew how it ended, but he just hadn't written it yet. And then the pages would come. This was probably before Fed Ex. I think somebody from Columbia put them on a plane, and then one of our guys would pick them up at the Cleveland airport. The same way we sent the film home, because we'd finish the day's work and somebody would put the film on the plane.

OUTRÉ: It's amazing to think how you guys ever did the show. It had to be a lot of hard work.

MILNER: It was a ton of work. And you could never do it again because, in those days, the networks didn't keep such a tight rein on production, and by the time the network saw one show, we were in the next town. If they didn't like it, it was too bad. And in those days, too, the producer had creative control of the product. Now the networks maintain all the creative control. They would never let a company have the kind of freedom you'd need to do that kind of a show.

OUTRÉ: That freedom is shown in a lot of the storylines. A lot of Silliphant's scripts seem so far removed from what you normally think of as television.

MILNER: One of the many talents that Stirling had, he recognized things as happening before the general public knew they were happening. For instance, he wrote a show about LSD before anybody knew what LSD was.

OUTRÉ: Tod took the LSD in a beer that had been spiked with it, in a show set in Philadelphia.

MILNER: Right. And nobody knew what he was talking about. He wrote a show about far right-wing fascist groups in America before anybody was really aware of that phenomenon. He was a trend-setter.

OUTRÉ: And a lot of the characters that you guys ran into seemed to be victims of an uncaring society, and it was only Tod and Buz, and later Linc, who seemed to give a damn, and because they cared, the characters came to some sort of resolution.

MILNER: Mad magazine did a story about us in which we went into a town where Mary Worth lived. And Mary Worth had solved everybody's problems in the town. So there was nothing for us to do, so we just had to go on.

OUTRÉ: So many of the shows featured long speeches. Was that a problem for the actors?

MILNER: We learned them. We didn't use cue cards or Teleprompters, so those long speeches had to be learned. We had a lot of actors on the show with theater background.

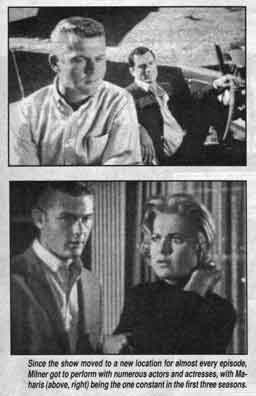

OUTRÉ: What was it like having so many big-name stars guesting on the show? I understand many of them asked Stirling to write scripts for them.

MILNER: It was a very popular show in the trade. And it was a great training ground to work with people like Nehemiah Persoff, and Rod Steiger, and Lee Marvin. Good actors and good directors.

OUTRÉ: Any particular episodes that you feel represent your best work or stand out in memory?

MILNER: Probably that show in Philadelphia where I took the LSD.

OUTRÉ: Do you recall the episode filmed in Weeki Wachee, Florida, about the mermaid?

MILNER: That was kind of spooky making that show, because the only way to enter that underwater arena, at the time we did it, was through a water-filled tunnel that seemed a hundred yards long. It was probably 30 yards long. It was dimly lit and there were breathing tubes interspersed in the tunnel every 15 to 20 feet. And you were swimming in the dark and looking for a breathing tube, and if you didn't find the breathing tube, you really got the feeling you were going to drown down there. That was the first time I did it. I didn't like it very much, but I got used to it.

OUTRÉ: Do you own copies of any of the shows?

MILNER: Columbia House put out a collection of about 20 of the shows, and I have those. And, I don't do it very often, but occasionally, I'll look at one and have no recollection of it, and seeing how the story comes out comes as a total surprise.

OUTRÉ: Were the stories of strife between you and George Maharis true?

MILNER: There wasn't really strife between us, but we never really connected, we didn't have much in common, so we didn't socialize together, but there were no sparks on the set or anything like that.

OUTRÉ: Do you ever hear from him at all?

MILNER: I saw him about three years ago. Vanity Fair did a piece on the golden years of TV and they picked the best Western, cop show, and they picked our show, and we did a photo layout in the desert, and that was the last time I saw George.

OUTRÉ: Was it any different when Glenn Corbett came along?

MILNER: Yeah, Glenn and I really got a long well. We became very good friends. And prior to Glenn, this you might find interesting, Bert Leonard wanted to use Robert Duvall. And we used Robert Duvall in two episodes, and of course he was marvelous. But CBS wouldn't accept him in the role on a week-to-week basis because they felt he was too offbeat. And that was when they hired Glenn.

OUTRÉ: Glenn was a good choice.

MILNER: Oh, yeah, and a wonderful man. He was such a nice human being.

OUTRÉ: How do think TV drama today compares with what you guys were doing on Route 66?

MILNER: lf you watch TV today, I think you have to be selective. I think there are things that are on that are wonderful. I love Law and Order. I watch whenever I can. I think there are other good things on. But there's nothing really to compare with Route 66.

OUTRÉ: I wonder, if Silliphant were alive today, if he could even sell the networks a pilot for something like Route 66?

MILNER: The problem with guys like Silliphant and Bert Leonard, in a sense, they're dinosaurs, and they're not used to networks telling them what to do. Even if they sold the shows, there would be such conflict about the content of it that it wouldn't work. That happened with Bert Leonard. He wanted to do a two-hour reprise of Route 66 - a reunion show with George and me - but it never came to fruition. The reason that I heard it never happened was because Bert couldn't get along with the network. He was used to having control.

OUTRÉ: What did you think of the re-make made during the '90s, with Dan Cortese, that ran as a summer replacement for about four shows?

MILNER: I thought the guys were very good, but I didn't care for the storyline.

OUTRÉ: Why did Route 66 end? Was it ratings, or did Silliphant want to go on to movies?

MILNER: No it wasn't Silliphant wanting to move on. You have to remember that Route 66 and Bert's other great show, The Naked City, were the last shows on television in which the networks had no partnership. They didn't participate in the profits. They were wholly owned by Columbia and Bert Leonard. And they were really anxious to get us off the air so they could replace us with something that would make more dollars for them. We were the last hurrah of the independent producer that was really independent

OUTRÉ: Did you ever see Stirling Silliphant again in later years?

MILNER: When I was the host of a morning radio show about ten or 15 years ago, here in San Diego, Stirling came to town promoting his book. He was writing an adventure series, Steel Tiger, and I had him on my show. It was wonderful. We spent an hour talking about old times, and talking about his new works. It was a shock when he died. He died before he should have.

OUTRÉ: Mr. Milner, thanks for talking with us.

MILNER: It was my pleasure.

OUTRÉ - No. 24 (2001)

If you are a Route 66 fan, please consider joining the discussion group at:

groups.io Route 66 TV