|

|

Ohio66 presents an in-depth look at the circumstances surrounding the departure of George Maharis from route 66 in the middle of the third season.

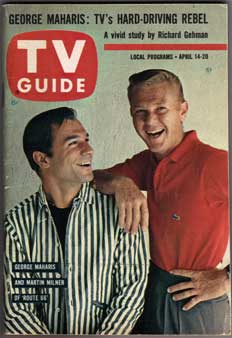

GEORGE MAHARIS: TV's HARD-DRIVING REBEL

HE'S ALWAYS RACING HIS MOTOR

Route 66's George Maharis travels at a headlong pace, but his direction is uncertain

Whenever I think of George Maharis—which for the sake of my nerves is as infrequently as possible—a fantasy materializes in my mind. I seem to be watching a sequence from a horror film called “The Method Creature.”

The stars of this offbeat epic are Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Ben Gazzara and several other mumbling types. They play mad beatnik doctors. Their evil old hunchbacked servant has stolen various human parts from Forest Lawn. They have stitched these members together and their creation now lies before them in the back—alley coffee shop where they carry on their eldritch misdeeds.

“Mmph,” says Brando to Newman, meaning: “Throw the switch, Paul.”

“Mmph,” says Newman to Gazzara, meaning: “You throw it, Ben.”

Gazzara throws the switch. As the three men watch, scratching themselves and pulling at their T shirts, the body on the table stirs. It gets up. It staggers about. It mumbles. They shake hands phlegmatically. They name it George Maharis.

Now, now, all you millions of George Maharis fans, don’t throw the nice magazine on the floor. This is not to say, or even to imply, that George Maharis is a monster. He has a monstrous appetite for life, he is ferocious in his likes and dislikes, he is appalling in the headlong pace at which he travels, and frightening in his scorn for authority; but he also is a living (Heavens, how he lives!), breathing (in great Tomwolfeian gasps), functioning (continually), and in many ways quite likable human being.

“Inger Stevens—she’s a friend of mine—says, ‘George, you’re like a coiled spring,’ ” Maharis told me not long ago. “She’s right. I’m like a coiled spring. People say, ‘George, relax.’ I ought to. But I’m like eight cylinders and I always got them going.”

So he is. But he also is the creation of the Brando-Newman—Gazzara school of acting, the kindergarten of which is the Presley—Fabian-Frankie Avalon class. This group first came into prominence when Marlon Brando broke into the candy store of entertainment some years ago and then beckoned other hoodlum types in after him-not to steal, but to vandalize, throwing out style, taste, good manners, sensitivity and, above all, intellectuality.

They are not anti-intellectual, exactly; they are more non-. They do not try to understand; rather, they dig, which means they feel rather than grasp. Instinct is all important, and flash judgment just below it.

Thus one, hearing a snatch of a Beethoven trio over a hi-fi, instantly concludes that he is conversant with the entire range of Beethoven’s work. He then talks as though he is—and he scoffs at, or puts down, those who actually have made a study of music. It is his conceit that anyone who has made a thorough investigation of any subject has wasted too much time in detail work to really feel. This is part of his rebellion, rooted in his distaste for the society he feels is oppressing him.

Thus Maharis: “I can hold up a discussion with anybody. I know. I have this friend, he has everything I never had—education, training, degrees. He used to talk to me about art, and so on—all that kind of stuff, books, politics. And I was amazed how even though I didn’t have the vocabulary and the facts, I had the instincts ....”

And again: “I never learn lines. I read a script through and put it down and forget it. I don’t think. Then I come to a scene and start rehearsing it, and I start talking, and somewhere along the line I make a connection, come to something I feel, and then I put my finger on it, and that’s it .... I lack discipline as an actor,” he finishes, proudly.

Actually, he lacks more than that. He lacks the ability that comes as result of care. In his haste to let his instinct govern he often becomes grotesque. When a script calls for him reach a peak of anger, astonishing things happen to his face. It seems to run off in many directions.

Someone once remarked that when Samuel Goldwyn became angry, his face resembled that of an old monkey eating a lobster: His jowls and throat worked painfully, as though poked from within by spiny shells and claws. When Maharis gets angry before the TV cameras, he resembles a young monkey eating a lobster.

This makes no difference whatever to women. The spectacle of his inner feelings somehow finds its way to the basic depths of the very young girl, the not-so-young-woman and even the covered-dish-social group. On Search for Tomorrow he played a gambler who mistreated his wife. Women refused to believe he was all bad.

“Old ladies would write in and say, ‘She should go back to him, he’s a nice boy, he’s got those nice long eyelashes’” Maharis says, an entirely plausible note of wonder in his voice. “One time there was a scene where I busted down her bedroom door. So they wrote in and said, ‘Why shouldn’t he? He’s her husband.’”

Right now Maharis is rapidly becoming one of the Nation’s foremost symbols of sex in the raw. One day in January I watched him shooting on location in Phoenix, Ariz. While the scene was being set up I wandered over to a group of teen-agers who had been developed by sun and orange juice into living posters for The Good Life. They actually were shivering in the deliciousness of standing within 20 yards of Him.

It did not matter to these children, none of whom was over 15, that Maharis was totally out of sight in another room, not learning his lines. They were there, in The Presence. They kept patting their little permanent waves.

So did their mother; that is, the mother of three of them, a trim blonde of about 36, coiffed with careful casualness, wearing one of those limp wool suits that all Phoenix women seem to have been crocheted into at birth.

My question as to why these future members of the Phoenix Junior League dug Maharis (I often use words like that to establish rapport with my subjects) brought only giggles and sighs. The mother was more articulate, but not much more.

“They saw him a couple of days ago and came home and haven’t done their homework since,” she said, more in empathy than in disapproval. “I don’t know why.”

She did know why. She was as helpless as her offspring. In telling me her name she first misspelled it and then hastily, testily corrected herself, clearly resenting my intrusion into whatever dreams she may have been having of wandering blissfully hand in hand with her daughters’ hero.

But Maharis is something more than a love-image. Our conformist, mechanized society responds to the antisocial. Like one of his old idols, John Garfield, to whom he has been compared, there is a touch of the outlaw about him. He is a young marauder in neatly capped teeth: Part of it is pretense, part of it is his real personality.

Maharis abhors nearly everything that the rest of us accept as part of our lives. He refuses to own an overcoat. For a long time he dressed in nothing but sweaters, shirts and dungarees: “You could wash dungarees, didn’t have to press them.” He loathes eating with tools.

“They say I’m a vegetarian, but I’m not really,” he told me one day. “I can’t stand the chores of washing dishes, all that. I don’t understand having to cook food before you eat it. I go into a supermarket and buy five pounds of apples and eat three before I’m out. I’ve always gravitated toward things I could just pick up and eat—carrots, lettuce, other vegetables. It saves time .... ”

Wherever Maharis goes in his job on Route 66, he takes along a portable refrigerator. Inside are heads and heads of lettuce, bunches of radishes, bags of tomatoes and apples. On top of it are bottles of vitamins and safflower oil, cans of bone meal and protein from the sea, honey, peanut oil and other things consumed by food faddists. Yet they are not there entirely because he once worked in a health-food store and became addicted.

Maharis eats these things out of an ingrown fear of losing his strength. As he admits, he is fundamentally insecure. He is a nonconformist not simply because he hates organized society; he is one because he feels he has to protect himself.

PART II - April 21, 1962

"On the Road," by Jack Kerouac, is not so much a novel as an uncontrolled eruption celebrating delinquency, canned beans, broken speed laws and marriages, irresponsibility, jazz and junk. It is the bible of the rebellious beat generation. Truman Capote once said of it, “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

Nevertheless many people see significance in it. So, too, people see significance in the acceptance of Route 66, a TV show in which two young men go shuttling back and forth across the country in a sports car which is, ironically enough, a kind of status symbol in the society they are rebelling against.

There is no connection between “On the Road” and Route 66, asserts Herbert B. Leonard, producer of the latter, who took time off from his labors one day early this year to give me a five-minute interview.

“I never heard of the book until a few weeks ago,” he said, staring intently at a cutting machine, on the screen of which George Maharis, one of the two stars, was busting a villain in the nose.

“The show was my conception and Stirling’s,” he went on, referring to Stirling Silliphant, the writer. “We were trying to show two young guys searching for values in the modern world.” Since Kerouac’s characters are searching mainly for kicks and hub caps to steal, this is at least one instance in which TV’s aims are loftier than those of the modern novel.

“We created the show with George in mind,” Leonard said, turning back to his artistic labors over the cutting machine and ending our interview.

If Route 66 therefore is not an example of art imitating art, it certainly is one of art imitating nature, for the character George Maharis plays is very like George Maharis himself.

He plays the part with such driving intensity that people are inclined to overlook the fact that as an actor he leaves a good deal to be desired. They also are inclined to forget that Martin Milner, who plays a rich young man teamed up with Maharis’s slum-background young man, also is very much in the show.

George’s love affair with George

Maharis has run away with the production from the beginning. He has become one of the most sought-after young actors now working, Warren Beatty notwithstanding. He earns around $1500 a week. He could be earning twice that, and more, if he could get out of the series and accept some of the film parts producers are hurling at him.

No one is less surprised by his success than Maharis.

“Ever since I was a kid, people always have liked me for some reason or another,” he told me recently while discussing himself, a favorite pastime of his. (“George’s love affair with George will stand the test of time,” a photographer has said.)

“I don’t know what it is I have,” Maharis went on, “but people have just sort of taken to me. They think I’m going to be conceited, but when they get to know me they kind of see things in me they wish for themselves. . . . I can kind of speak for them, you know?”

When Maharis speaks for “them,” it is with the voice of protest against the stratification of society, and against poverty and lack of privilege. He was born the son of Vasidos Maharis, an immigrant from Greece, who at 32 married an 18-year-old girl, Demetra Stranis, also an immigrant.

George was the third of six children; his older brother Bob is a production assistant on Route 66. There were two sisters; one of the brothers is dead. George is 32, although he says, “My agents say I’m 28.”

The family was well-to-do, at first. Vasidos Maharis, whose Americanized first name is William, had three small restaurants around Astoria, Long Island, where they lived. Then according to George, he lost his businesses.

“There he was with his wife, five kids then, and nothing. It became like a panic—bill collectors knocking on the door and all that kind of stuff, my mother working at odd jobs. She worked nights as a cleaning woman, she got pneumonia and almost died, she had to go away to a rest home.”

The consequences of the poverty were George’s feelings that others in school looked down on him. “I never felt that anybody liked me or that I belonged. Because I had these holes in my shoes, I tried to pull all kinds of tricks so people wouldn’t see I was poor .... ”

He went to Flushing High and left to spend 18 months in the Marines. “We went to Cuba, or was it the Virgin Islands? No. San Juan, where’s that? Puerto Rico. Or was it Cuba? Anyhow, I did my boot camp at Parris Island. I’m terrible at names, dates, places. I can’t remember any.”

This is part of Maharis’s resistance to the mores of our society. Memory connotes school; school connotes authority. Still, he returned to school when he left the Marines. He graduated. By then he had discovered that he had a fair singing voice, which by the way he still does; he has made his first LP record for Epic label, and although his style is imitative of Frank Sinatra’s, he is far and away better than the rock ’n’ rollers who currently pollute the air waves.

At about the time of graduation he also had discovered something else. Although he probably was not consciously aware of it, the intensity of his shame and the feeling of rejection bad begun to come out as animal magnetism. As he told me, people took to him. When he went to get singing or acting jobs, casting directors noticed him.

The classes conducted by Lee Strasberg in New York City seem to attract the likes of Maharis. Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Ben Gazzara, all similar types, studied with this master of the mysterious Method. Maharis studied with him for three years, off and on. He now says that Strasberg was the only good teacher he ever had—perhaps because Strasberg’s aim is to let actors feel their way into parts and not to intellectualize. If there is one thing Maharis is good at, it is not intellectualizing.

“I don’t read,” he told me, “because when I pick up something I want to finish it, and what book can you finish at a sitting?”

Although he paints, he never has had any academic training. “I’m sort of an expressionist,” he said. “I express what I feel ....”

His first break in television came when he did a parody of Marlon Brando on a Mr. Peepers show. At the time he had seen Brando do only one part, he told me. To have seen more, of course, might have forced him to think.

The only time Maharis appears to think is when he is devising ways to get away from the girls who are always chasing him (he has no plans to get married for a long time, he says), or when arguing with directors.

Because whatever it is that he has comes from within, he is continually embroiled with these harassed types. He objects to the way lines are written because he cannot feel them. The directors feel that if he were to examine his parts more carefully, he would be able to summon the proper moods. It is a never-ending struggle.

I feel rejected

In reality, the fights are a cover-up for Maharis’s uncertainty. Although he is now on the verge of becoming one of the foremost actors in the country, he feels a resurgence of the fears and doubts he had as a boy.

"Now I get irritated quicker," he said to me one day recently. "I get nervous twitches I never had before. I feel rejected much more than I did when I was a kid. I feel that people don’t look at me as I used to be .... I’m kind of an image, not a human being. I’m very uneasy when I’m in a room full of people, I want to get away. I never had trouble sleeping before, now I do ....

“I don’t want to be an image, I want to be what I am .... ”

The trouble is, Maharis has not yet decided what or who he is. Asked what he thinks of himself as an actor, he said, “Not bad. I think I’m honest most of the time. I fall into traps some of the time, I’m not quite as broad as I could be, not as far-reaching. Not yet. Maybe some day.” And then he made a remark that summed up all his worrying restlessness, all his guilts and anxieties, and yet revealed that there is more to him than just a relentless, unthinking energy.

“You know what I feel?” he said. “I can’t wait till I get old .... ”

TV Guide - April 14, 1961

If you are a Route 66 fan, please consider joining the discussion group at:

groups.io Route 66 TV